Crisis Communication: Advanced Care Planning when in Extremis

Problem

Patients that come into the Emergency Department (ED) in extremis often are asked about advanced care planning (ACP) preferences under stressed, pressured conditions in which quick decisions need to be made and action must be taken. Despite the recognition that discussions around code status are as important as invasive procedures, there is no standardization to the process. Unlike informed consent, there is no guideline, educational tool, or aid to help standardize ACP discussions.

Background

The wicked problem of advance care planning in the critically ill ED patient necessitates an effective communicator who has confidence in leading such a discussion and also a provider who seeks to understand the patient’s experience. Provider and patient priorities do not always align which can lead to mistrust or negative interactions. In one study, cultural discrepancies about attitudes towards healthcare in general, religion, spirituality, and death and dying are highlighted as potential complicating factors. Providers must juggle competing principles of ethics to provide their patient with appropriate care. Multiple stakeholders (providers, family, patients, nurses) have vested interest in ACP discussions in a pressured, time-sensitive, high stakes environment that currently is addressed by an inappropriately scripted opt-out model with little room to assess patient values and fails to include key elements of a normal informed consent.

Process

Gather.

How is crisis communication occurring in our emergency department? During the gather phase, information was collected via informal interviews of expert faculty and nursing (in the Emergency Department and Palliative Care Department). From the interviews, 5 key principles (arranged in chronological order) about crisis communication emerged.

Treat symptoms first

Think about physical space: move the conversation out of the resuscitation bay and to a consult room if possible.

Understand patient perspective

Standardization of language: appropriate v. inappropriate language

Give a recommendation to the patient based on their co-morbidities

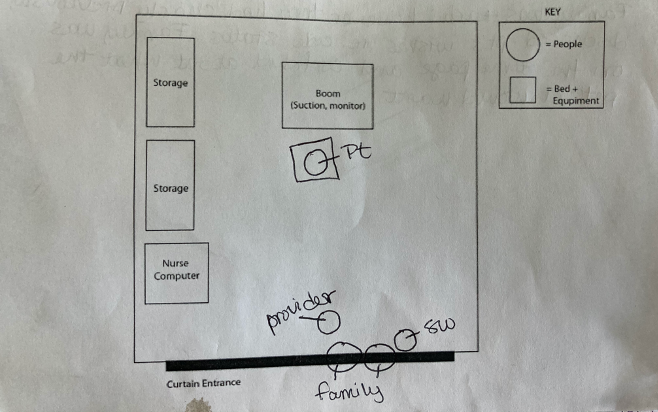

Observational data was collected by social workers who often were present for conversations in the resuscitation bay. This information was expanded to not only include the content of the conversation, but also the physical space and arrangement of people in the room.

Lastly, data was collected from non-medical community members. Seniors were willing to express preferences for end of life care in a semi-public setting. 64% state their physician has NOT initiated a conversation about end of life care. Of those, many wished a healthcare provider would review their end of life options with them.

DEFINE.

After analyzing the information collected, it was determined the problem was three-fold.

Lack of Appropriate, Standardized Language

There is little to no education for ED providers about what constitutes appropriate language when having ACP conversations.

Lack of a Formal Recommendation

There is no standardization for what constitutes an appropriate ACP conversation, ie. giving a formal recommendation at the end.

Distracting Environment

Discussions in the resuscitation bays are fraught with noisy interruptions and are sometimes the first time ACP discussions are initiated.

Prototype.

With data in hand, the iteration and prototyping process began. Guiding design principles for each prototype were usability/patient understanding, standardization of language, aesthetics, and legibility.

Aesthetics refers to the color and physical appearance of the final product. Legibility ensures a reader can easily read and comprehend the text. Legibility is increased when principles of visual hierarchy are applied such as typography, indentation, bold, italics, proximity, and page placement.

PROTOTYPE 1.

Initially, the model was a sheet of paper, inspired by the standard hospital informed consent form. The form contained appropriate language as decided upon by hospital palliative care leaders in both the palliative care department and emergency department. Various forms of visual hierarchy were used to ensure the text was legible.

Testing and Feedback

Though formatted, eading a paper with small print is difficult for patients in extremis (pain, respiratory distress, nausea). Legibility and usability could be improved.

As a piece of paper, a new form would need to be printed for each patient for infection control. It is highly unlikely for a provider to do this while simultaneously stabilizing their patient.

Prototype 2.

The second iteration reimagined the physical manifestation of of the final project. Each question was isolated on one small waterproof card to facilitate comprehension and overall usability. A binder ring secured the sheets together allowing a provider to either go through the collection in a sequential or a la carte fashion.

Standardized language was pulled from the informed consent form directly.

The material used for printing was a matte-finish heavier weight paper that allowed for disinfecting between use.

TESTING AND FEEDBACK

The new design was favored for its usability, however the text remained dense and less legible than the first prototype.

Next phase of iterating targeted legibility and aesthetics.

Prototype 3 and Final product

Scroll to see all 8 cards.

The final product uses color and italics to increase legibility. The formatting with one question or statement per card helps with usability and the overall minimalist aesthetics. And, the language on the cards reflect the standardization desired by palliative care experts. This discussion aid enables providers to learn the appropriate language for ACP through on-shift learning.

Testing and feedback

The final product met all guiding principles and served as a scaffold for having advanced care planning discussions in the emergency department.

The production of the final product was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic.